Philosophy and Tom King: Existentialism in Batman #23 (2016)

By Steve Baxi - In a June 2019 interview with iFanboy, Tom King joked that he always writes the same story and hopes to make it better each time. Thus far, his work is divided into four eras and while each has their own identity, in some respects they all ultimately build on the same story King is always telling: a story about existential dreads that need to be overcome by facing reality. In education, philosophy, and writing execution, Tom King is an existentialist through and through. Every comic he writes centers on the base idea of how one chooses to exist in a world they have been thrown into. How does Scott Free learn to live in good faith? How does Batman decide what a good life is? How does Vision practice his humanity?

Batman #85 - Tom King/Mikel Janin/Jordie Bellaire/Clayton Cowles

In her history of existentialism, At the Existentialist Café, Sarah Bakewell writes “the word ‘existentialist’ brings to mind a noir figure staring into the bottom of an espresso cup, too depressed and anguished to even flick through the pages of a dog-eared L’être et le néant” (Bakewell, 173).

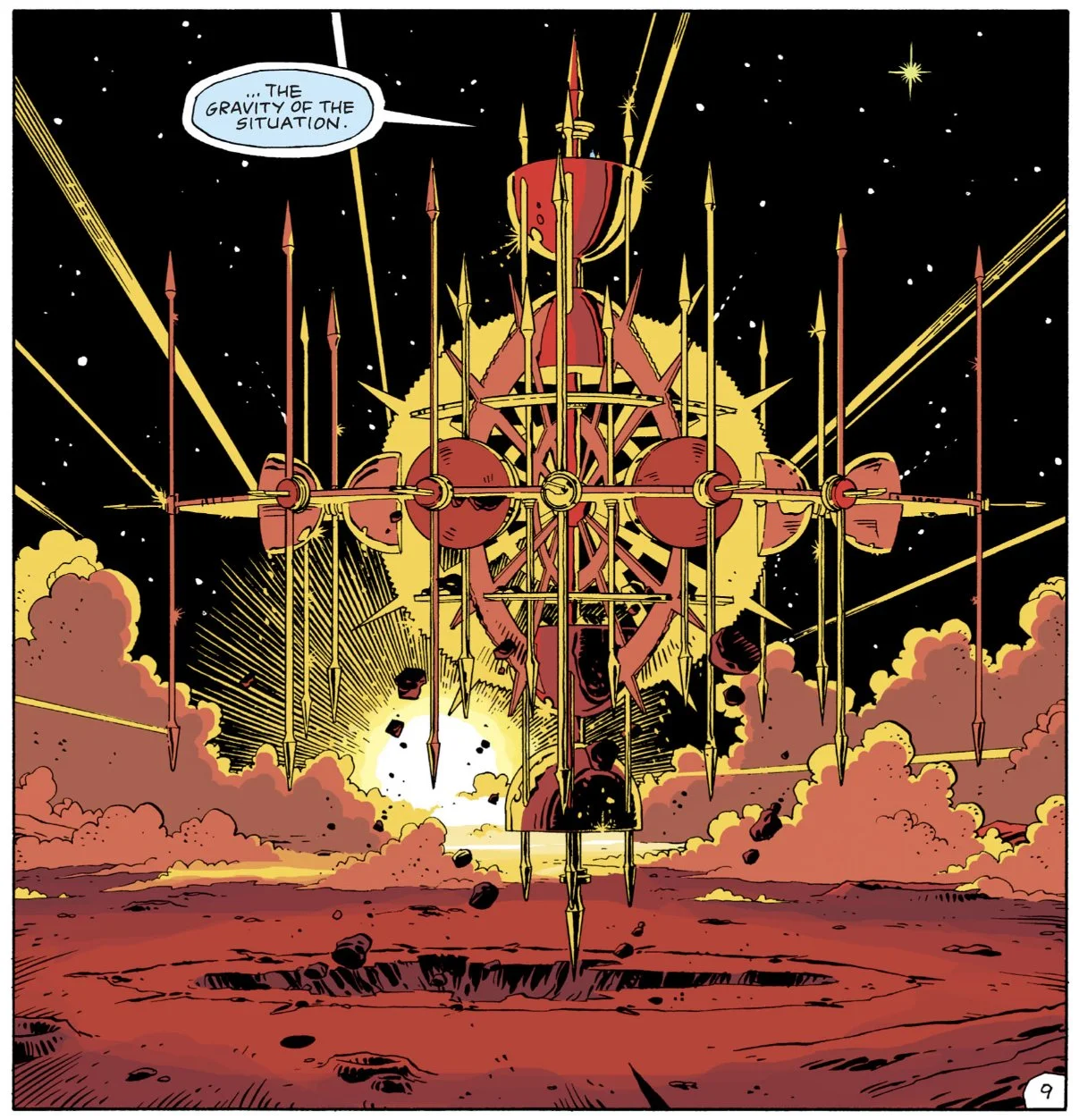

Batman #23 - Tom King/Mitch Gerads/Clayton Cowles

The caricature of existentialism here is not far off the mark of a Tom King comic: sad heroes staring out windows, usually in a 9-panel grid. While that repeated formula is something King has acknowledged, the reason it works is because it performs his central idea so well. To live is to choose who you want to be over and over again on an endless loop. To paraphrase Albert Camus, one of the many philosophical inspirations for The Vision, one must imagine Tom King happy.

While Tom King is not the first or only writer to take influence from the most widely accessible form of popular philosophy available, he is certainly the one who makes it the most overt. Ed Brubaker, for example, writes very clearly existentialist influenced crime comics, often with entire pages of characters musing about their embodied experience in the world.

Reckless - Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips/Jacob Phillips

The difference with Tom King is that the influence is not the subtext as much as it’s the text itself. Catwoman quotes Wittgenstein, The Omega Men features quotes by William James, Scott Free explains the Kantian critique of Descartes, and King himself has called his Batman run Kierkegaardian.

At its heart, a work of existentialism aims to be practical, it wants to demonstrate how to live. According to Kierkegaard, “no philosophical system, no merely intellectual approach to life, helps a human being to live in the world, to make decisions, to become himself” (Carlisle, 137). An existentialist view is one where “Life becomes ideas and the ideas return to life” (Bakewell, 30). This is the spirit Tom King channels into his work: attempting to take whatever idea or symbol a character represents and forcing it to crash down into our world of fragmentary experiences. He takes the assumed subtext of Batman being suicidal and makes it the text of the story.

Batman #23 — “The Brave and the Mold” by Tom King, Mitch Gerads, and Clayton Cowles — is, I believe, the most concise account of this idea-meets-reality approach to storytelling at the center of all of King’s comics. The story follows Batman and Swamp Thing’s investigation into the murder of Alec Holland’s father and develops the idea of grief, where ultimately Swamp Thing’s “merely intellectual approach to life” meets the bitter reality of facing down death. King’s writing here resembles a classic existentialist novel, often with scenes that don’t escalate plot as much as they repeat the rhythms of the everyday or normal world until he breaks the comfort established with Swamp Thing’s killing blow on Headhunter.

The story has several key features in King’s work: Lyrics as dialogue, 9-panel grids, and repeating beats. By this point, King is well practiced in all of these techniques, in particular how the 9-panel grid can be used to incorporate all of them. While there are reasons worth exploring as to the origin of these techniques, like for example how King chooses songs to avoid giving characters plot relevant dialogue during action sequences, what is most interesting me is how King’s view of the 9-panel grid becomes the philosophical linchpin in this story’s concept of grief, and his work as a whole.

In various interviews, King has said he loves comics that are in boxes and in The Omega Men, he developed a view of how the 9-panel grid as “bars on a cage” represents the reality of the world comic book characters inhabit. King does not break the formula here; every page operates on the natural rhythm of the grid, creating center panels that house the main idea while allowing for scene transitions at every page turn.

Batman #23 - King/Gerads/Cowles

The narrow boxes force Batman and Swamp Thing into their own “prison cells” isolated from each other to create both distance and two distinct philosophies of death. For Swamp Thing, death is compartmentalized and abstract. For Batman, death is an embodied experience, death is something that determines your ability to live at all.

Batman #23 - King/Gerads/Cowles

However, what makes King’s work fascinating with respect to his existentialist tendencies here is that the comic is not merely told in a 9-panel grid but rather thinks of the world in the terms of a 9-panel grid. Kyle Rayner’s speech in The Omega Men #12 is telling as he opines about how the grid forces distinctions to take place, separating the story from us.

The Omega Men #12 - Tom King/Barnaby Bagenda/Romulo Fajardo, Jr./Pat Brosseau

According to Kyle, the grid is merely “bars on a cage” and that imprisonment, that isolation, is a falsely constructed distinction between people, ideas and reality itself. Repeated use of the grid is designed to show that the separation being depicted is an individual, emotional and ideological choice in how we view reality and each other. It is a safe framework to distance ourselves from the ideas of the work of fiction.

A Tom King comic attempts to break that separation, break that cage in some way. In a 2018 interview with Word Balloon, King described his debut novel, A Once Crowded Sky, as an attempt to bridge the gap between story and reality. This thematic fascination has developed over the years where Mister Miracle is about the nature of reality through our perception of it, Strange Adventures questions the narrative we tell ourselves to live with our reality, and Rorschach blends the fiction with the real to address the weight each exerts on the other.

This need to question the separation, draw attention to the bars on the cage of the story, helps explain how King wants to bring the ideas of grief in Swamp Thing crashing down to the reality of our experiences.

Batman #23 - King/Gerads/Cowles

In Batman #23, Swamp Thing and Bruce discuss the nature of grief, how the death of one’s parents can leave them unnerved like Bruce or how death can be rationalized into the more metaphysical scheme of the universe, as with Swamp Thing. Bruce’s way of coping since his parents’ death is, to put it mildly, absurd. A fact King has addressed in his run, both in Thomas Wayne’s plea not to be Batman (Batman #22) and with Bruce’s letter to Selina explaining just how childish his war on crime appears (Batman #12). The death of his parents defines him, haunts him, and even drives him a little crazy.

Swamp Thing on the other hand has all the answers. He explains how death is more than dust-to-dust and does not warrant human grief. Rather, in a more harmonizing way, Swamp Thing asserts that the state of all things is to change, for the body to grow, die, and nurture the soil that sprouts new life. This sounds right, this sounds like the advice we’re given when we ourselves grieve. The problem is that Swamp Thing’s enlightened answer does not feel, ironically, very natural. It might be correct in some ways, but it's not how real people immediately process a traumatic event. The contrast here is that while Batman may have been driven a little crazy by the death of his parents, that ought to be expected. What makes less sense is for someone to suffer trauma and appear completely at peace immediately.

The narrative strategy, then, is to use the 9-panel grid not merely to show the contrast between these two but to demonstrate Swamp Thing’s own fatal flaw in his world view. The grid, the isolation and separation, the bars on the cage, are forcing a distinction, a separation between the idea and the lived world. He is boxed into something that compartmentalizes his feelings without facing the reality of them. There is a routine, a rhythm to his actions and the murder mystery plot that houses this story. It piggy-backs off the natural rhythm of the grid to create a sequence of events that feel very comfortable, very normal. However, that comfort ultimately has to break eventually. After all, while Swamp Thing speaks of being at peace, the very fact that he’s attempting to catch the murderer invites us to ask what he will do when he finds him.

One useful aspect of the 9-panel grid is that you can move the story very quickly. Each panel has only enough room for one singular focus and the rest of the space can be filled with dialogue or captions. Each row of panels can often tell a mini story, setting up a focus object, giving a beat, and then allowing for a payoff. By the time you reach the end of the page, you can accomplish a majority of a story’s plot and thematic progression. King, however, does the opposite. His dialogue is minimal, his characters move slowly through time from panel to panel, and the focus is usually on mundane conversation like why Batman needs a car. This is all an attempt to build a rhythm, a sense of routine that accents the already building thematic idea of isolation. Every panel reads quickly, naturally flows into the next, every line of dialogue is concise and then repeated often by way of chapter titles. Like Swamp Thing’s response to the death of Alec Holland’s father, the entire comic is remarkably well rehearsed.

This creates another useful aspect of the grid: creating a break. With the rhythm so natural, with each panel no larger than the last, every event feels organized and normal. This allows for the writer to usually create large story shifts by disrupting the panel grid with dramatic changes in layout. Once again, King does the opposite by not breaking his formula. Instead, the big break is Swamp Thing choosing to kill Headhunter in cold blood once he finds him without any change in how the story was laid out so far.

The idea here is that Swamp Thing’s idealized picture of grief is presented as sane, normal, rational and carries that sense of ease throughout a very basic, very concise panel layout that supports his demeanor. The grid is as organized and easy to follow as Swamp Thing’s logic about death. The action is clear and even just like his world view. However, when Swamp Thing kills Headhunter, within the cool and calm rhythm of the layout, there’s suddenly a level of unease. “This is normal, this is natural,” argues the panels. Whereas the brutality of the murder seems to show otherwise. Ultimately this conflict is what King is after, this separation between the calm order of our separated and distinct thoughts in contrast to the reality of our actions.

Batman #23 - King/Gerads/Cowles

The final page of the story demonstrates this beautifully, as one final 9-panel grid ends with Swamp Thing’s grassy remains in panel 9 without any border or closed off box. There’s no panel to lock it in but it's framed by the same structure as every other grid in the issue. This break in the sequence is Swamp Thing finally allowing for a human reaction, something that isn’t imprisoned or held back. As Bakewell said, the idea returns to life. One part of the prison breaks when Swamp Thing finally does something that seems more human and less rationalized, less boxed in.

Reading Tom King comics can be difficult. Adam Strange is a war criminal, Mister Miracle tried to kill himself, Wally West lost control of his powers, and Swamp Thing murdered someone in cold blood. King’s work likes to take the concepts and escapism of characters, and bring them down to our reality. However, this is not an arbitrary choice in an attempt to make the characters darker. Rather, it’s presented as a way to deal with real conflicts and emotions through the fantastical reality of comics. We know what making a mistake and lying about it feels like, but there is something cathartic about transforming that mistake into a world changing superpower with disastrous consequences. Our emotions feel like the end of the world, so why not give them to people who could actually end the world?

While there might be some sourness in reading Swamp Thing murder someone, the reality is that the fiction is making an extreme out of our very real emotions. If you faced the grief of a loved one dying, a part of you wants to lash out the same way Swamp Thing does. Allowing him to do that gives form to the experience. Tom King is able to present this reality in mainstream superhero comics better than most because he allows the characters’ existing darkness, flaws and history to inform the emotional reality he wants to place into the book. Batman as the embodiment of death and facing darkness contrasts perfectly with Swamp Thing, the character entirely about the cosmic struggle of life and death on earth.

In Batman #23, the panels truly become bars on a cage that limit the scope of how Batman and Swamp Thing are able to communicate with each other and handle their respective traumas. In the final panel, all we are left with is the reality of how these emotions take hold of us and how death animates the value of life. This story does not run the same length or spectrum of emotions as King’s other work but familiarity with the tools demonstrated here can help understand the greater details of his career at large.

Steve Baxi has a Masters in Ethics and Applied Philosophy, with focuses 20th Century Aesthetics and Politics. He creates video essays on pop culture through a philosophy lens and requently tweets through @SteveSBaxi.