Man Without Fear...By The Year: Daredevil Comics in 1995

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1995. Oklahoma City is bombed by white supremacists, Windows 95 is released, the FDA approves Chicken Pox Vaccines, and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin is assassinated. People are listening to “Gangsta’s Paradise,” watching Clueless and reading Daredevil.

Written by D. G. Chichester [as Alan Smithee] (338-342), Warren Ellis (343), J.M. DeMatteis (344-347)

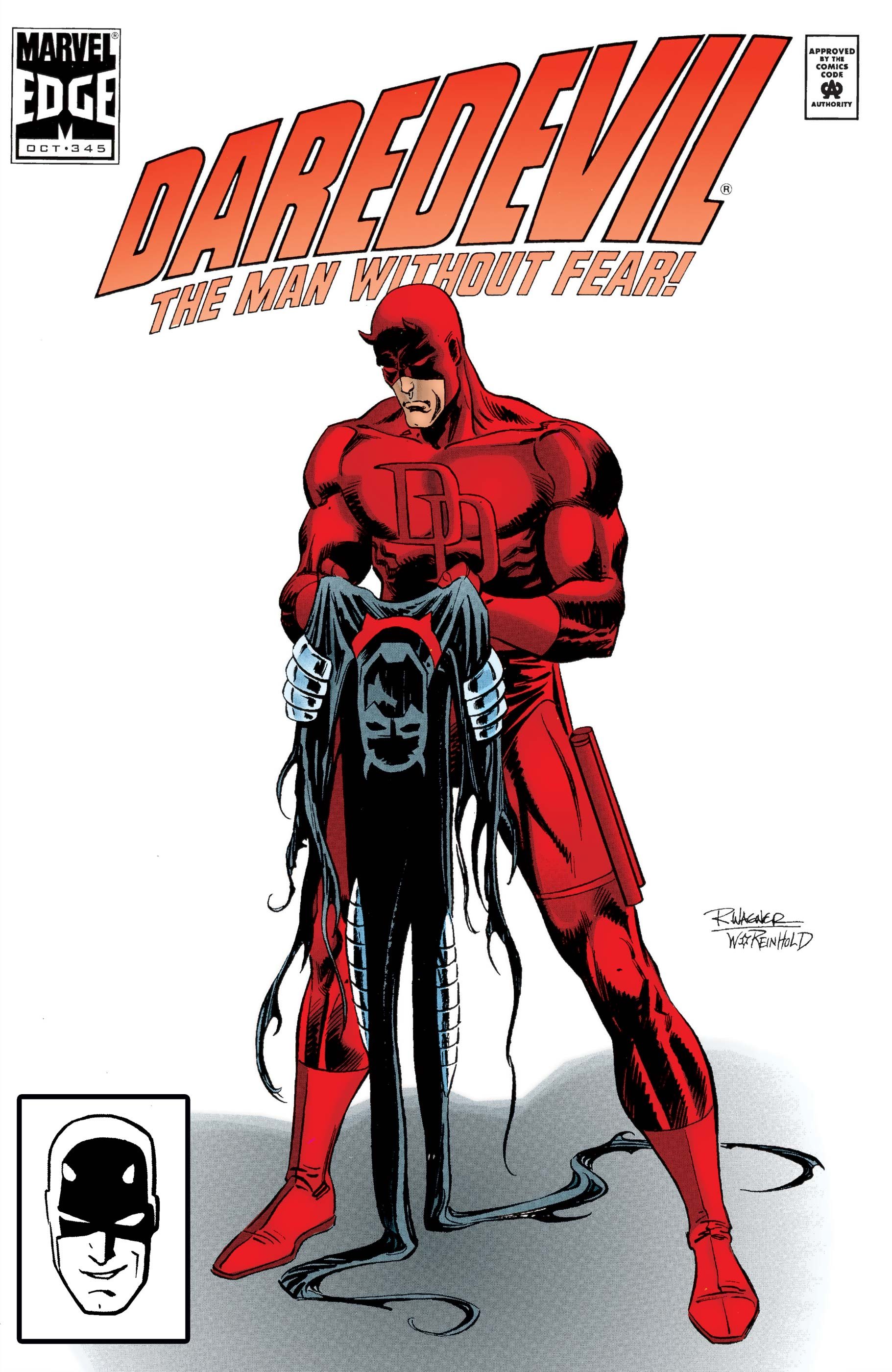

Illustrated Alexander Hubran (338-340), Keith Pollard (341-343), Arvell Michael Jones (343), Ron Wagner (344-347)

Inks by Ande Parks (338-340), Don Hudson (338-340), Bud LaRosa (339), Rodney Ramos (339), Marie Severin (340), Art Nichols (341), Tom Palmer (342-343), Bill Reinhold (344-347), Ron McCain (347)

Colors by Max Scheele (338-339, 341-342, 344-347), Paul Becton (338), John Kalisz (340, 343)

Lettered by Bill Oakley (338-343), NJQ (338-343), Jon Babcock (338), Jim Novak (344-347), Ul Higgins (347)

Daredevil has identity issues. Most costumed crime-fighters probably do, but Matt Murdock goes through these problems more than most. It wasn’t so long before he was wearing an armoured costume and posing as street con-artist Jack Batlin that he was the amnesiac “Jack Murdock” and someone else was wearing the Daredevil costume.

This is someone who moved to San Francisco for a fresh start, only to have spectators (correctly) guess at his true identity back then too. This is someone who faked having (and being) his own twin brother “Mike Murdock'' to cast suspicion of Daredevil off himself. Even Matt Murdock is often a disguise in itself, posing as a “helpless blind attorney” so no one will know his true abilities. Through the years Matt has been through many identities – and a parade of writers trying to pin him down – so it's no wonder he undergoes mental breakdowns so frequently.

A similar identity crisis was happening behind-the-scenes at Marvel. The rapid and volatile spectacular boom was beginning to burst, and Marvel was struggling to control its swelling empire. In 1994 they had acquired Heroes World Distribution to be their own exclusive distributor, which set off a chain reaction of other distributors failing until only Diamond remained (Heroes World itself proved too inexperienced to survive). At the same time, Marvel’s list of titles was so large, it abandoned having the single Editor-in-Chief of Tom DeFalco, and divided up its universe between five separate “group Editors-in-Chief.”

So Marvel’s monthly titles were grouped within 5 broad sections, such as the X-Men titles or Spider-Man books. One of these was “Marvel Edge,” an imprint for Marvel’s “edgier” street-level books like The Punisher, Incredible Hulk, Ghost Rider, Skull Kill Krew and, of course, Daredevil. In some ways, “Marvel Edge” acted as a precursor to imprints like Marvel Knights or Marvel MAX, codifying this territory as a more “mature” domain in Marvel.

It was edited by Bobbie Chase, one of the highest-reaching female editors at Marvel, who disliked Chichester’s direction and planned to hand over Daredevil. But in the internal shake-up, Chichester caught wind of his upcoming dismissal, and had his final storyline (after a hiatus to work on Elektra: Root of Evil) unceremoniously credited as “Alan Smithee” in protest.

You’d expect such contractually obligatory issues from an embittered writer to be more experimental, or even curious in their half-heartedness, but Chichester’s final storyline is strangely straightforward. It involves an old partner of the Kingpin called “Kruel,” whom Wilson Fisk betrayed and left for dead, slowly working his way back to Kingpin by stalking bystanders of their confrontation (who ignite memories in the amnesiac Kruel). It just so happens all these bystanders are established supporting characters from Daredevil, prehistoric versions of Ben Urich, Foggy Nelson, Karen Page, Kathy Malper and Glorianna O’Breen (who was last heard of quietly leaving Foggy during Ann Nocenti’s early run).

Kruel functions as a silent avenger and spectre of past sins, being portrayed with a ghoulish skeletal face (although Alexander Hubran depicts it as a simple scar, while Keith Pollar has a full sunken-face – another example of an identity crisis). These supporting characters were each going through a private crisis of their own – Ben Urich condemned to a puff-piece, Karen Page offered a sleazy acting gig etc. – whom Kruel reminds them of. He also reminds Matt of all the lives he has touched, even as he hides behind a fake name. Although Chichester creates an interesting subversion with Matt (understandably) assuming he is at the centre of Kruel’s targets, when in reality he is uninvolved.

Chichester narrates how this is “an arrogant theory, presuming he’s the only possible connection. But Matt’s never been short on arrogance.” It’s an interesting case of subverting the centrism of Daredevil (where everything happens because he is the protagonist) and have him be entirely incidental to this serial killer. Yet Chichester’s doesn’t find anything to replace this subversion with. There is no reason all of (and entirely – aside from the line cook) Daredevil’s supporting characters were bystanders to Kingpin and Kruel’s confrontation, except that Chichester simply orchestrated this coincidence, and had the Kingpin “wipe their memories” to eliminate any small continuity errors. Matt maybe “arrogant” for assuming he’s the only connection, but it isn’t an unreasonable theory considering there aren’t any others. Plus, Matt’s theory actually means he seeks out Foggy Nelson before Kruel gets to him, making his “arrogant theory” actually work to his advantage.

Or at least for him and Foggy. Poor Glorianna is not so lucky. Kruel throws her off a building when scoping out the (apparently dead) Matt Murdock’s apartment. Glorianna becomes another addition in the tragically long line of deceased Daredevil love-interests, including Elektra and Heather Glenn (even more will be added in time). Glorianna was also Foggy’s love interest – their burgeoning relationship an underrated aspect of Born Again – but this storyline primarily focuses on Daredevil’s angst that another of “his women” has been killed. Gail Simone would collate the “Women in Refrigerators” list in 1999, but even 4 years beforehand, Glorianna’s death feels like a cheap and unnecessary move.

I’ve been pretty harsh on Chichester’s tenure, but one aspect I really like is him foregrounding Daredevil’s compassion. A recurring theme of his run has been “second chances,” with Daredevil protecting and forgiving many of the criminals he hunts down, or even emphasising “all the while Daredevil never let go of [Kruel’s first victim] Robert Ashbury’s hand.” So it feels unfair that Chichester’s replacements disregard his “armoured Daredevil” as being too bloody-thirsty, with inner-monologues about street-punks being rapid animals he must put down. Several story-threads of Chichester’s were abandoned – Foggy working for the corrupt Fisk TV station, Karen Page teaming up with newly fired S.H.I.E.L.D. Agent Garret in hunting down cybersex-crime – but it's this dismissal of the “Jack Batlin” phase as a mental breakdown which must sting the most.

Chichester’s run is transitioned by an issue from Warren Ellis, just beginning his comics career (that would eventually culminate in several allegations of sexual coercion). “Recross” (Daredevil #343) features Matt randomly blacking out and waking up in the middle of fights, with duelling internal voices debating who he actually is. Matt wears his “lawyer suit” instead of his armoured costume here, which Ellis labels a “fetishist riot cop” outfit and says of Jack Batlin “a fake identity. A fake Murdock. What was I thinking?” Daredevil has had so many identity changes, so many writers, that he’s not sure who he is anymore.

Tackling this question is legendary writer J.M. DeMatties, perhaps most famous for the Spider-Man story “Kraven’s Last Hunt.” That featured Kraven the Hunter going through his own identity crisis as he wishes to finally, properly, kill Spider-Man and assume his mantle. DeMatties’ Daredevil contains similar motifs and brooding atmosphere, with Matt left unmoored by his own spiralling thoughts. They are only further complicated when his armoured costume is torn up (forcing a return to his red one) and a “new” Daredevil appears, claiming to be the “real” original one, and wearing the Yellow costume to prove it.

Daredevil only wore his Yellow costume for 6 issues before changing it to red. But it symbolises the early Silver Age origin of the character, before the character was steadily darkened throughout the ‘80s, back when Daredevil was a simple swashbuckling Stan Lee superhero. Ben Urich thinks how “this was Murdock in the early days… before Urich even knew him. When Daredevil’s spirit was lighter,” the jolly Yellow Daredevil embodies a “Golden Age” when moral lines were clear and identities were solid. Of course, Daredevil has been playing with his identity since the beginning, and those issues were hardly short on melodrama, but Daredevil warring with his “Yellow self” over who is the authentic Daredevil makes for a fascinating arc.

It also helps that DeMatties is a good writer, who paces out this story and fills it with neat character betas. He nicely balances out the ponderous mystery of this new Yellow Daredevil, alongside exhilarating fight sequences that are kept silent and kinetic with Ron Wagner’s artwork. For as Matt chases this Yellow Daredevil around the city, he also must fight the vicious “Sir,” a misogynistic serial killer who detests “weak” femininity and covets masculinity, even (as in Kraven’s Last Hunt) stripping Daredevil of his costume since it’s a “vessel” for his prime macho power.

“Sir” heavily plays into DeMatties’ themes, with him stealing Matt’s costume and thinking how “it’s not the face beneath the mask that matters – it’s the mask itself.” Although DeMatties continues this in an uncomfortably outdated way with the “twist” that Sir is actually a transexual man, who despised his own “weak femininity” (and implied abuse) so much that he “became” his abusers and despised his old self. DeMatties’ probably only viewed this as a tool for his themes on identity, but that is part of the problem with seeing trans experiences as purely thematic instead of lived experiences, and only perpetuates harmful stereotypes of transexuals as delusional or diseased, who transitioned for the sake of trauma or “revenge” instead of simply becoming their true selves.

Regardless of the rocky road to it, DeMatties spotlighting Matt’s identity crisis makes for interesting reading in the back-half of 1995. It’s hardly the first time Daredevil has been left distraught from being pulled in so many directions, but DeMatties (mostly) elucidates it with visceral attention. Daredevil has enough history that pulling in this piece of forgotten iconography holds a strange symbolic profundity. 1995 ends with Matt realising he was the Yellow Daredevil, his fractured mind meaning he couldn’t recognise himself, just as the Yellow Daredevil didn’t know he was Murdock. Matt repeatedly cutting up his life has left it in tatters, and now the pieces are collapsing in on themselves.

As this series has hopefully shown, there have been many Daredevils over the years. Matt comes to understand he is “all of them,” from the jolly Yellow saviour to the menacing Red avenger, and the weight of this revelation leaves his hollow and catatonic on Karen Page’s bathroom floor. She and Foggy Nelson now know that Matt Murdock is “back,” but what this really means – and who Matt or Daredevil really are – is an eternal, open-ended question.

Read classic Daredevil Comics!

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.