The Man Without Fear...By The Year: Daredevil Comics in 1981

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1981. Prince Charles marries Lady Diana, Sandra Day O’Connor becomes the first female justice on the Supreme Court, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was assassinated and AIDS was first clinically observed. People are listening to “In the Air Tonight,” watching Indiana Jones, and reading Daredevil.

Written by Frank Miller

Illustrated by Frank Miller

Inks by Klaus Janson

Colors by Doc Martin (168), Glynis Wein (169-174, 176-177), Bob Sharen (175), Christie ‘Max’ Scheele (175)

Lettered by Joe Rosen (168-177)

“Close your eyes. Let the night touch you.” So opens Frank Miller’s run on Daredevil, beginning 1981 as its writer and penciller. It is a damp and murky world, describing the “moan of a freight barge” and “maggot-ridden garbage” of New York, a sublimely disgusting city that only Matt Murdock’s super-senses are fully attuned to and can stomach. ‘70s Daredevil writers referred to New York as “Fun City,” even if the nickname was often tongue-in-cheek about the Big Apple’s bustling nightlife. But Frank Miller dug deeper into the rancid urban environment that came at Daredevil from all sides. Daredevil has long struggled to find his own place. But Frank Miller relocates it back on the streets, building a whole new architecture around Daredevil that will last for years to come.

Now Frank Miller remains one of the – if not THE – biggest names in mainstream comics. And it was his work on Daredevil which provided him a foothold in the industry at 24, resulting in one of the most famous and acclaimed superhero runs of all time. Miller’s Daredevil holds the same prestige as Claremont’s X-Men or Watchmen as works which reinvented the perception of comics. Not only does this Daredevil carry such colossal historical baggage, but so does Frank Miller himself, who after his great prominence has flamed out in embarrassing and horrifying misogyny and Islamophobia, especially for works like All-Star Batman and Robin and Holy Terror!.

Frank Miller might be past his prime – both creatively, and the relevance of discourse around him – but he remains a legendary figure as one of the few “voices” instantly recognisable outside the industry. Enough ink has been spilled on reckoning with Miller (entire books, like Paul Young’s Frank Miller’s Daredevil and the Ends of Heroism, have been dedicated to it) but he is unavoidable when dealing with Daredevil, taking the every-two-months book back to “at last, monthly!”, as the cover of Daredevil #171 boasts. Miller made an impact on Daredevil specifically and the industry generally, the ripples of which are still being dealt with, for better or worse.

Unfortunately, I cannot be a contrarian and claim Frank Miller’s Daredevil does not hold up. It does. And it’s a clear step above most of what has come before. The transition is smoother than expected, as Roger McKenzie’s earlier writing laid the groundwork for such maturity and Miller’s writing can be awkward at first. But despite following on from what came before, Miller has a clear, cohesive vision of Daredevil based upon expanding his core aspects, instead of simply copying what had come before.

One way is the depiction of Daredevil’s foes, particularly the assassin Bullseye. Previous appearances had Bullseye grow increasingly obsessed with out-performing Daredevil. Miller turned this “professional” rivalry into a manic personal obsession, having Bullseye’s erratic behavior linked to “a cancerous growth – a tumor – in his brain” that creates painful hallucinations of Daredevil all around him. In these issues Bullseye is a quasi-unstoppable sadistic force, gravitating towards anything that will best position him against Daredevil.

Bullseye has become one of Daredevil’s most notorious foes, but another Daredevil enemy gets reappraised here; The Gladiator. McKenzie already reworked Melvin Potter into a delusional, child-like man dependent on his social worker in Daredevil #166, and Miller picks up this thread with Matt Murdock defending the Gladiator on trial. As Bullseye is made more psychopathic, Gladiator is given mental issues to become sympathetic. Even as Gladiator is tempted to “return,” he realizes how vacuous his “unbeatable” armor is. Bullseye returns after harassing a tailor to make him a new costume, but Melvin throws his old one away, telling Matt all it makes him feel is “alone.”

Melvin is tempted since an (inadvertent) Gladiator lookalike, Michael Reese, is stalking around New York in a spiked fetish gimp suit, preying on “naughty girls” whom he sadistically “punishes.” Miller brings in this sexualised violence – heavily coded as rape – which is responsible for legal aid Becky Blake’s paralysis. Becky also did not report the crime due to her traumatic humiliation, a depressingly real anecdote. Frank Miller is not known for being the most sensitive writer, and this does awkwardly conclude with Daredevil experiencing a similar threat when he’s pinned down by Reese that “made [him] understand at least a part of what [Becky] went through” and encouraging Becky to testify. But although Reese himself is utterly over-the-top, Miller is surprisingly tactful here, allowing characters to wallow in their genuine messy feelings towards such trauma.

Between the determined criminal (Bullseye) and the oafish redemption (Gladiator), Frank Miller also reinvents the Kingpin into Daredevil’s recurring foe. Originally a Spider-Man villain, John Romita Sr. designed Kingpin as an imposing Wall Street baron who controlled New York’s criminal underworld. But he had been used sparingly since the 1960s – a total of 5 story-arcs over the entire 1970s – and relegated to another generic supervillain. Miller introduced the Kingpin in Daredevil as already retired, self-exiled to the Japanese mountains with his wife Vanessa, banning the mention of his old American life. But when Vanessa approaches Nelson & Murdock to broker a plea deal with the U.S. Government, she is quickly kidnapped, and Kingpin is dragged back to New York. Frank Miller established Kingpin outside the status-quo, only to force his rebirth into it, which some of his henchmen welcomed. Miller described it as taking the original clear-cut Romita Sr. Kingpin, and adding the shadows from lighting up a cigarette, making him become “mine.”

But Frank Miller’s original creation arrived with his first issue (Daredevil #168) with Elektra. Miller admitted to copying Elektra’s femme fatale from Sand Sarif of Will Eisner’s The Spirit, and her namesake from Greek Mythology, who swore revenge after the murder of her father Agamemnon. In Daredevil, Miller mines Matt’s unexplored college years and retroactively implants Elektra as his passionate girlfriend, who he’s so infatuated with he immediately reveals his powers to her (far quicker than Karen Page ever got). Elektra is a largely sheltered daughter of a Greek Ambassador, who is killed in a botched hostage crisis, sending Elektra into despair and anger which eventually morphs her into a highly-trained assassin.

Elektra represents an alternate path for Daredevil. The death of his father motivated Matt to take up justice, while the death of Elektra’s father made her a cold-blooded killer. Now the two are on opposite sides, lovers turned to enemies, who also cannot resist the dormant feelings. This dynamic electrifies 1981, as even when Elektra isn’t directly involved she haunts Daredevil’s thoughts and protects his flesh when The Hand (her old ninja clan) are sent by the Kingpin to assassinate Matt Murdock. Matt reminds Elektra of her former idyllic life, which she resents him for but also wishes to preserve. Something similar happens with the Kingpin, who after Vanessa’s apparent death delusionally mutters to himself “the Kingpin must make them pay.” Once cast in certain vengeful roles, it is hard to shake them off.

All of Daredevil’s cast seem “tempted,” including the supporting cast. Becky Blake is tempted to stay silent about Reese, before Matt encourages her to speak up. Foggy Nelson despairs that the Legal Storefront is going bankrupt doing pro bono work and seems poised to give up, before Matt also rejuvenates him. The only one he can’t seem to reach is Heather Glenn, Matt being too preoccupied with Elektra to keep up with his party-loving girlfriend. Heather’s exasperation with Matt is treated a bit as a joke – “Heather’s left me… for the third time this month” – and she seems simply bored that Matt is not around. Heather is mostly an obstacle for Frank Miller’s new love-interest Elektra from taking over, but Miller does include poignant scenes of Heather feeling herself pushed out of the narrative.

Another small Daredevil player given more screen-time is Turk Barrett. Turk has popped up a few times as a henchman in Daredevil, but now he becomes a regular contact for Daredevil to comically interrogate in the underground. Turk even runs towards the window when Daredevil arrives in Josie’s Bar. Even when Turk tries battling Daredevil in some battle-armor, Daredevil dispatches him in two panels amidst other concerns.

Turk is a “punk,” a classic Frank Miller word, and 1981 generally increases Daredevil’s street presence of “punks,” prostitutes and cab drivers. The narrator tells us “This is New York City. But if you’re thinking it’s all bright lights and big money and all that glittery junk you seen in the movies, well, you’re in for a shock. ‘Cause it isn’t a playground. It’s a battlefield.” And Daredevil is the guardian angel of this urban battlefield, called a “shadow among the shadows that cloak the city he loves,” intrinsically a part of its underbelly.

Frank Miller even puts his own stamp on Daredevil’s origin story, introducing Stick in 1981’s last issue, Daredevil #177. Stick is a mysterious, gruff blind man who trained Matt to hone his super-senses, and a new session with Stick involves psychedelic hallucinations of his childhood that appear much more horrible than previous incarnations. Here, Jack Murdock has chained Matt with expectations, neighbourhood children intensely bully Matt for being a bookworm, and Matt even lashes out at the old man he saved from the radioactive truck, screaming “you old fool! Look what you’ve done to me! You’ve blinded me!” It even culminates in a huge Lovecraftian horror representing Matt’s “private devil.” Matt must work through this fear and anger to appease them, becoming once again the “Man Without Fear” and regain his composure.

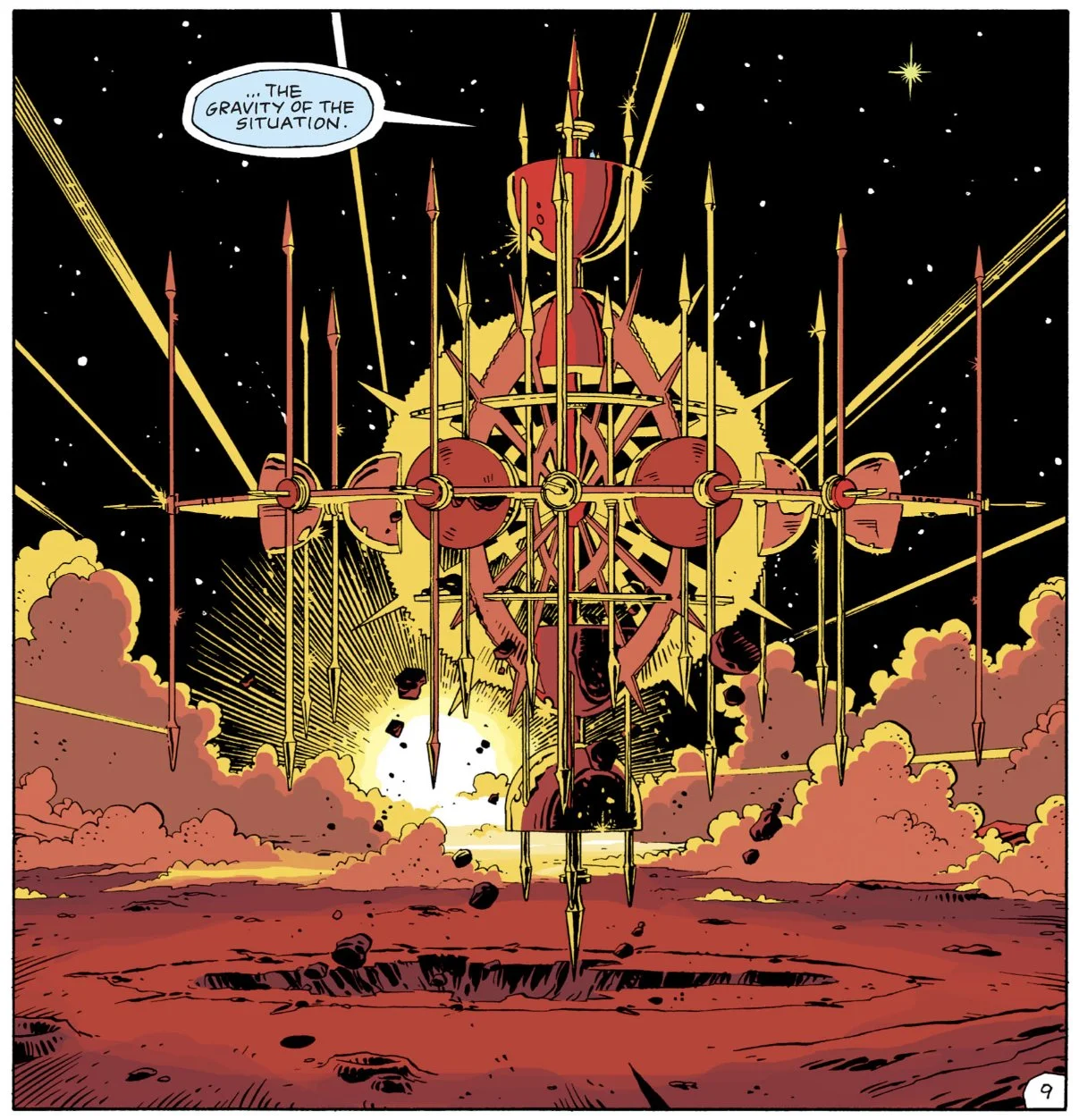

Frank Miller did not succeed on Daredevil purely by making it “gritty” and “serious.” Instead, it holds up because of the writing and pacing of these issues, being invigorated with renewed purpose. Miller’s own pencils actually become looser and more idiosyncratic throughout his run, foreshadowing his blocky deconstructive artwork in Sin City or The Dark Knight Returns. Yet his layouts provide crisp, clear action sequences with interesting perspectives and shadow during the dialogue. More importantly, Miller gives plenty of silent repeated panels that let the characters breathe. Several moments involve characters facing a moral dilemma – like Gladiator considering his past armor, or Daredevil deciding if he should let Bullseye die – that utilize the spacing and repeated panels of comics to lend them extra weight.

This same technique, surprisingly, is used for many comedic moments. Frank Miller definitely increased the grittiness and psychodrama of Daredevil, but work isn’t with moments of levity and comic relief. As Bullseye and Daredevil fight, two cinephiles discuss The Maltese Falcon uninterrupted. Or Daredevil’s constant, predictable, interactions with Turk. Or how in the hunt for Stick, multiple groups barge in on informant Wall-Eyed Pike one after the other, leaving him a despondent wreck by the end of it. Frank Miller’s legacy is over making Daredevil dark and serious, but he does not completely sacrifice certain light entertainment.

1981 is a pivotal year for Daredevil, and even more could be said about it. Frank Miller molded the template that was already there, keeping the same determination (and arrogance) that makes Matt such an intriguing character. He sprinkles in additional sex and violence which were uncommon to mainstream comics, making Daredevil stand sharper on edge. All his added elements of Daredevil – Kingpin, Bullseye, Elektra, even Gladiator – have been weaved together into an operatic (but more street-based) epic surrounding Matt Murdock. Like it or not, there is no going back now.

Read classic Daredevil Comics!

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.